Mesopotamian Art and Architecture

10 min read

History of Mesopotamia was characterized by numerous invasions and conquests which also greatly influenced art and architecture. New peoples and rulers introduced their own sociopolitical systems or adopted the established one, while similar process also took place in art and architecture. Thus art and architecture in Mesopotamia are commonly divided into different periods: Sumerian period, Babylonian period, Assyrian period, etc.

Religion and religious organization played very important role in both art and architecture in Mesopotamia. Monumental sacral buildings - the temples were the centers of Sumerian city-states and were both religious and administrative centers throughout the Sumerian period. Leading role of the religion in Sumerian society and political system was also noticeable in Sumerian art which was dominated by religious motifs, deities, mythological beings and priests. Stone and wood as natural sources were very rare and the Sumerian artists and artisans mostly used clay which explains the soft and round appearance of the Sumerian sculptures in compare to the Egyptian statues.

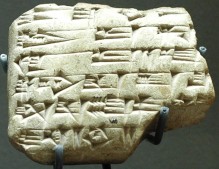

About the same time as the Sumerian cuneiform script also emerged Sumerian cylinder seal, a cylinder engraved with different images, text and sometimes even a picture story which was used as a mark, signature or confirmation. Impressions of cylinder seals can be found on a wide range of surfaces such as pottery, doors, clay tablets, bricks, etc. The cylinder seals remained popular for a long period after decline of Sumerian city-states. Greek historian Herodotus reports that everyone in Babylon carries a seal in his work The History of the Persian Wars (c. 430 BC).

Sumerian art and architecture at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC reveal the signs of decline but Sumerian culture, art and architecture entered into a new era after the arrival of the Semitic peoples during the Early Dynastic Period. The arrival of the Semitic peoples which took place slowly also resulted changes in the Sumerian language but latter was used in literature until the 1st millennium BC. The Early Dynastic Period is notable for the worshippers, small statues of individuals were placed in front of the deities in the temples. Majority of the statues of worshippers has been found in northern Mesopotamia which was settled by Semitic peoples in greater extend than other parts of Mesopotamia. The finest examples of Sumerian art from the Early Dynastic Period were found in Tell Asmar (site of the ancient Sumerian city of Eshnunna), Iraq in the 1930’s. The period that followed the Early Dynastic Period reveals greater tensions towards naturalism although the fragments of the so-called Stele of Vultures found in Telloh, Iraq, depicting victory of Eannatum of Lagash over Enakalle of Umma from about 2500 BC indicate move towards stiffness.

With the conquest of the Sumerian city-states by Sargon of Akkad about 2340 BC Mesopotamia entered a new period, commonly known as the Akkadian Period during which occurred major changes in virtually all aspects of life including art. Changes in art which were probably influenced by non-Sumerian artists can be noticed already during the reign of Sargon of Akkad (c. 2334 - c. 2279 BC) although very little art works remained preserved. However, two notable heads of Akkadian statues discovered so far suggest great progress in portrait sculpture. Little also remained preserved of Akkadian architecture. It is known that Akkadians built palaces and fortresses and that they also reconstructed many Sumerian temples but due to paucity of architectural remains it is difficult to determine the architectural style during the Akkadian Period. In greater extent remained persevered only Akkadian cylinder seals which introduced new standards and are widely considered the zenith of the ancient Middle East art of cylinder seals. The Akkadian Empire was short-lived and collapsed two centuries after its establishment but it greatly influenced the Mesopotamian art and according to some authors established the basis of the “classical” Mesopotamian art which flourished until the collapse of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC.

Period following the collapse of the Akkadian Empire was characterized by full-scale Sumerian revival. The Sumerian revival can be noticed already in the votive statues of Gudea of Lagash (c. 2150 BC) found in the court of the palace of Adad-nadin-ahhe in Telloh, Iraq, although some authors consider them an intermezzo between the last Akkadian ruler and Ur-Nammu, the first king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. However, the inscriptions on Gudea’s robes are in Sumerian language and mention that Gudea built several temples which clearly indicates the revival of the Sumerian culture. Several Sumerian literary hymns and prayers were also created during the rule of Gudea and his son Ur-Ningirsu.

Opinions of scholars about the statues of Gudea might be divided but there is no doubt that Sumerian revival was in full-scale during the rule of the Third Dynasty of Ur. The period of Sumerian revival which dominated Mesopotamian art and architecture until the conquests of Hammurabi resulted in the creation of some of the greatest masterpieces including some of the most significant literary works such as the Epic of Gigamesh which is believed to be written about 2000 BC. Architecture was the predominant art during the period of Sumerian revival and is notable for the construction of the oldest terraced temples known as the ziggurats which probably inspired the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel. One of the finest examples of ziggurats from that period is the Great Ziggurat of Ur which was built by Ur-Nammu and his son Shulgi in 21st century BC (see picture below).

The Sumerian language was slowly replaced by the Old Babylonian dialect following the rise of the First Dynasty of Babylon, while the art works reveal a synthesis of the Akkadian art and the Sumerian revival. The First Babylonian Dynasty which reached its height during the rule of Hammurabi began to decline already under his successor Samsu-iluna, while the power in Babylon was assumed by the Kassites about 1532 BC. The only surviving artworks from the Kassite period are the kudurrus, stone documents used as boundary stones containing symbolic images of the gods and kings who granted the land as fiefs to their vassals. The kudurrus are mostly of poor artistic value but they are important sources for social, political and cultural history of the Middle Babylonian Period. The symbolic images of the gods present almost exclusively the Babylonian deities which means the Kassite adopted the Babylonian culture, while the images of kings granting the land to their vassals clearly indicate that the feudal system became the predominant social and political system in Mesopotamia.

Mittani Kingdom which emerged in Northern Mesopotamia about 1500 BC did not significantly contribute to the Mesopotamian art and architecture. Little is known about the Mittani culture and art, while the cylinder seals reveal influence of Babylon, Syria and Asia Minor. Like in Babylon, deities and worship are not longer the main motif which gave place to different animals, mythological creatures and so-called trees of life which represent a supernatural world.

Hittite Empire emerged in Asia Minor about the same time as Mittani Kingdom in northern Mesopotamia. Hittite Empire became one of the most powerful states in the ancient world by the 14th century BC and successfully competed with Egypt even under Rameses II, the Egypt’s greatest, most powerful and most celebrated of all pharaohs. The remains of the Hittite capital city of Hattusa, Yazılıkaya (both in today’s Turkey) and many other sites reveal magnificent monumental architecture as well as very impressive art which was dominated by portal sculpture and othostat reliefs.

Assyria first rose to prominence under Shamshi-Adad I (c. 1818-1781) who was one of the greatest Hammurabi’s enemies. His son and successor Zimrilim initially supported Hammurabi but later turned against him as well. Zimrilim is better known for building himself a palace in the city of Mari which became famous for its enormous size and splendid wall paintings already in ancient world. However, the Assyrian art from that period does not resemble the classical Assyrian art in the later period and was still under Babylonian influence.

Assyrian art and architecture greatly progressed by the middle of the 13th century BC. Tukulti-Ninurta I (c. 1233-1197 BC) who conquered Babylon and made Assyria one of the leading powers in the Middle East is also renowned for his building activities in Ashur as well as for constructing a new capital Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta which represents a prototype of Assyrian architecture. The art works and especially the cylinder seals from the Middle Assyrian Period almost achieved the quality and perfection of the Akkadian art although Babylonian influence (Sumerian revival) is still noticeable. However, for the first time can be noticed the distinctive Assyrian characteristics - animal motifs in first place lions and horses.

Assyrian art at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC still reveals different influences including Hittite, Hurrian, Syrian and Aramaean. Hittite influence in Assyrian art is obvious in portal sculpture and orthostat reliefs which are Hittite invention from the 14th century BC. Inscriptions on Assyrian art works in that period are written in cuneiform, and pictographic Hittite and Phoenician scripts what clearly indicates that Assyrian art which began to manifest itself in its distinctive forms in the 9th century BC has been greatly influenced by several different styles.

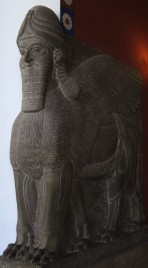

The distinctive Assyrian artistic and architectural forms developed in the 9th century BC during the rule of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC) who is best known his successful military campaigns as well as for building a palace in Nimrud (the biblical city of Kalakh) which was chosen as the new capital city. The Palace of Ashurnasirpal II was organized around three courtyards, while the palace walls were decorated with elaborate pictorial reliefs portraying the king on a military campaign, hunting, etc. containing inscriptions which reveal that he founded Nimrud and built the palace, and record his military achievements and other important events during his rule. The Palace of Ashurnasirpal II also contained portal sculptures and orthostat reliefs which were not placed outside like in Hittites but within the palace. There is also evidence that the palace was equipped with furniture decorated with ivory panels. Both reliefs and sculpture were glorifying the king and his achievements but an important feature were various animal forms such as lions, horses and winged beasts with bearded human faces.

The remains of the city and palace at Khorsabad (ancient Dur-Sharrukin or Fortress of Sargon) from the late 8th century BC built by Sargon II (721-705BC) who was one of the greatest rulers of Assyrian Empire reveal certain stylistic changes which are characterized by greater formality. The court moved to the new capital before the construction works were completed but after Sargon’s death in 705 BC his son and successor Sennacherib (704-681 BC) abandoned the city and moved the Assyrian capital to Nineveh where he built a palace which he named “The palace without rival”. The relief carvings in the Sennacherib’s palace are often considered the zenith of Assyrian relief carvings. Huge stone slabs were fully covered with relief carvings of important military and political events, while the landscape is an integral part of the scheme. Reliefs also feature inscriptions which record significant contemporary events.

Ashurbanipal (668 - c. 627 BC), the last great Assyrian king build a new palace in Nineveh which is commonly known as the North Palace and is notable for impressive relief carvings depicting his military expeditions, hunting scenes, political events, court scenes, etc. Ashurbanipal is better known for the Library of Ashurbanipal, a collection of thousands of clay tablets which is an important source for the Assyrian as well as for Sumerian, Akkadian and Babylonian history.

Mesopotamia after the fall of Nineveh in 612 BC flourished for the last time during the period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire which reached its zenith during the reign of Nebuchadrezzar II (604-562 BC) who was also a great builder. Nebuchadrezzar II built new temples, a palace for himself, massive fortifications, the famous Ishtar Gate and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon which are considered one of the original Seven Wonders of the World. Art works during Neo-Babylonian period remained mostly limited to the cylinder seals and terra-cotta figurines.